My home town of Alexandra was once the social centre of Central Otago, especially during the construction of the Clyde Dam in the 1980s. But social life seems to be cooling down now. Maybe it’s moved to the tourist hot spots of Wanaka and Queenstown - which didn’t even have their own supermarkets when we arrived in the area in 1979. Or perhaps the slower pace is just my perception: a product of my own advancing years. But what about its climate? Is that cooling or heating?

It’s an interesting part of the country to investigate that because it’s the nearest thing we have to a continental climate. It’s isolated by mountains on all sides and far from the moderating influence of the surrounding oceans.

In a recent post, I discussed the effects of climate change in Central Otago, and in Alexandra in particular. I speculated whether that could be a factor in the demise of the once hugely-popular outdoor skating on natural ice at the Lower Manorburn Dam on the town’s doorstep.

A crowded Lower Manorburn Dam during the 1959 New Zealand ice-skating championships.

Here I take a quick first look to see whether those statements are backed up by the official climate records. Climate statistics for New Zealand are available on the CliFlo database, which is maintained by NIWA. Anybody can register to access data from it at no cost using a (relatively) user-friendly interface.

Alexandra has one of New Zealand’s most extreme climates. It’s the driest, hottest (and near sunniest) in summer, near-coldest in winter, and one of the least windy places in the country. A few years ago I used data from CliFlo to create plots showing seasonal changes (as monthly means) in Alexandra’s temperature ranges, sunshine hours and rainfall. The plots are still displayed at the town’s website.

Here I look at how the annual means have changed over the years. There aren’t many other sites in the region with good data for more than 100 years, but Alexandra comes close, with measurements beginning in 1929. There have been several site changes in those last 90 years, but the five I used in the plots below are all at very similar altitudes and are all within a kilometer or so of each other.

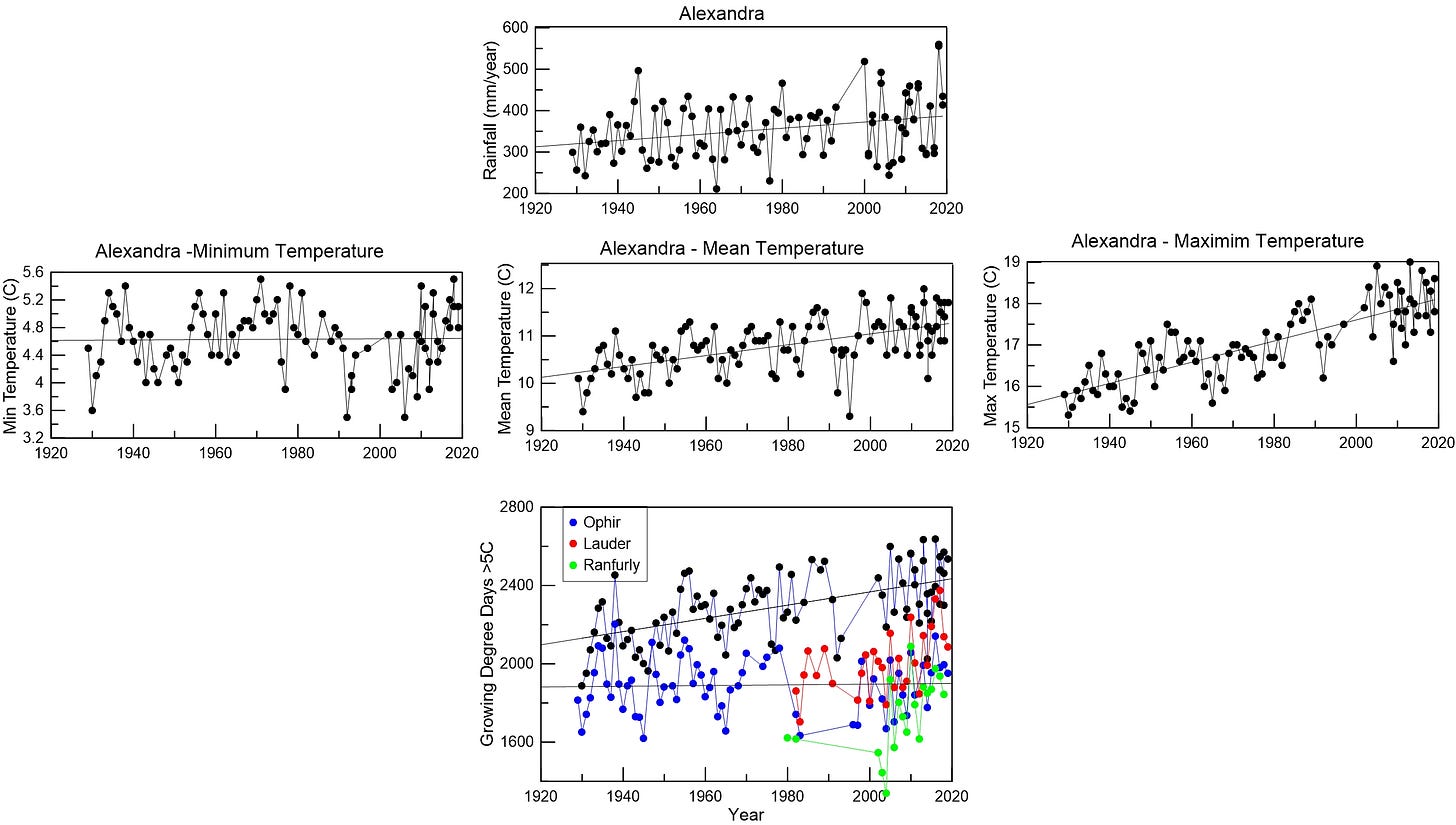

Below I’ve plotted summaries of changes in annual means of

Rainfall

Temperatures (minima, mean and maxima)

Growing degree days (GDD), a measure of the amount of warmth available for plant and insect growth that can be used to predict when flowers will bloom and crops and insects will mature. Here the GDD counts the total number of degrees Celsius each day is above a threshold of 5 degrees Celsius (other temperature thresholds can also be used).

There are a few data gaps, particularly in the early 1990s when it looks as if there might have been teething problems in the transition of responsibility for the database from MetService to NIWA. But a clear picture nevertheless emerges. Over the last 100 years, it appears have been getting wetter (top panel) and warmer (middle panels). The lines drawn on all these panels are linear fits to the data. While minimum temperatures haven’t changed much, maxima have increased by about 2C over the last century. Mean temperatures have increased by about 1C, which is in line with expectations based on other records, such as the famous (and once controversial) seven-station record for New Zealand. It was only controversial because a group of climate deniers didn’t want it to be true, and didn’t understand the intricacies of climate data analysis. They even went on to take NIWA to court over it. Of course they resoundingly lost their case, with NIWA being awarded costs. For the life of me, I still can’t understand why the deniers were so dogmatically determined to prove that there was no warming trend. Perhaps it just didn’t suit their agenda for some reason. To any atmospheric physicist, a lack of observed trend in the temperature record would have merely highlighted limitations in the measurement accuracy or their representativeness. With the current imbalance between incoming solar energy and outgoing thermal emissions, temperature increases are inevitable (because the measured extra infrared trapping due to the build-up of greenhouse gases is equivalent to the energy released from about 5 Hiroshima bombs every second).

The growing season, shown on the lowest plot, appears to have increased as well. But there I also show data for Lauder, and two surrounding sites: Ranfurly and Ophir. Incidentally, those two sites recently vied for having the coldest temperature ever recorded in any New Zealand town. Ranfurly’s -25.6C way back in 1903 has only recently been officially recognised as surpassing the previous record of -21.6C at Ophir in 1995 (making some people in Ophir very grumpy - I might take a closer look at this myself some time). Data from these other three sites is more limited - Lauder’s started only in the early 1960s - though the trend for Lauder and Ranfurly at least in recent years seems to match that at Alexandra.

But any increase in the number of growing degree days has been much smaller at Ophir, particularly over the longer term. That could be a real geographic difference. But maybe not. It also calls into question the accuracy of the data from either Alexandra or Ophir (or both). In a follow-up post, I’ll look at the number in greater details to see whether site changes at Alexandra (e.g., since 1983 several different sites used) have affected the data, as they did for the seven-station record.

I was involved with setting up a site in Pioneer Park in 2008, which we located there mainly to support educational initiatives associated with the nearby Central Stories museum. You can see current data from it here (and you can click on any icon there to see the recent history). The site doesn’t qualify as top quality “Tier 1” site. For one thing, the sensors are mounted too high above the ground - to avoid being damaged by vandals. Irrigation of the grass below in summer also affects results. And the sensors are too close to nearby buildings and trees, which sometimes shades them. Consequently, data from that site may be less accurate - so it’s designated as a “Tier 2” site. I’ve noticed that maximum temperatures there tend to be slightly cooler than at the other sites in town, while minima tend to be a bit warmer. Differences compared with the other nearby sites are typically about 0.5C.

What’s really needed is some other relevant proxy for the effects of climate change. Our long-established fruit growing industry could hold the key, but only if the same cultivars and farming practices have been used over a long period (or if there has been overlap when changes have been made). Good record-taking of parameters like the date of first bud-break, or date of first fruit-pick, etc would also be needed. If anybody has such data, I’d be very interested in analysing it. Please click the button below to pass this on to parties who may be able to help.

I’m interested to see if construction of the Roxburgh Dam in the 1950s, or Clyde Dam in the late 1980s had an effect. Long term changes in urbanisation, household heating, or agricultural practices - such as the historical widespread use of frost pots - may also have local effects.

Hopefully I’ll have more on this topic in a week or two. New visitors here can sign up below if you want more …