Ozone Benefits, Carbon Costs

How my part in solving the ozone problem contributed to global warming

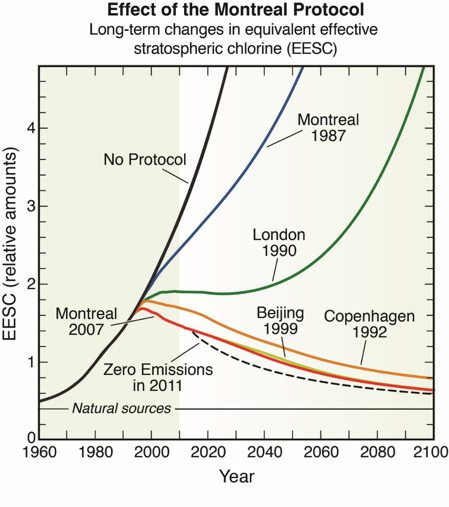

A strength of the Montreal Protocol on Protection of the Ozone Layer is its provision of mechanisms to report back to the Parties of the Convention on any changes in understanding of the issues. Three Panels are charged with this responsibility. For brevity, I call them the “Science Panel”, the “Effects Panel”, and the “Alternatives Panel”. The original 1987 version of the Montreal Protocol would have slowed down the build-up of chlorine in the atmosphere, but it would not have succeeded in reversing ozone losses and increases in UV without the reports from these panels, which resulted in strengthening of the original agreement. That strengthening was through subsequent Amendments and Adjustments to the Protocol, where more chemicals were brought under its control and phase-out schedules were accelerated. The most notable of these were the London amendment in 1990 and the Copenhagen amendment in 1992 (see figure below).

I wasn’t involved the “Alternatives Panel”, whose full title is the “Technology and Economic Assessment Panel” (TEAP). That panel comprises laboratory chemists and financial experts that investigate alternative chemicals to replace those that damage the ozone layer. But my close association with the other two panels goes back to the early 1990s.

My first involvement was with the “Science Panel”, or more formally the “Scientific Assessment Panel” (SAP) that reports back to the parties on our understanding of the relevant physics and chemistry of the atmosphere, and its effects on UV radiation at the Earth’s surface. It’s a joint initiative between the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). I was lead author for the UV chapters in their 1992, 1995, and 1999 Assessments, and co-author for their 2003, and 2007 Assessments. As part of that work, I attended three meetings in Les Diablerets, Switzerland and two in Washington DC, USA.

In 1994, after one of the SAP planning meetings in Washington DC, I took up an invitation to attend a meeting in Buenos Aires of the “Effects Panel” on my ‘way home’ to New Zealand (though the route was rather indirect). The Panel’s formal name is the “Environmental Effects Assessment Panel” (EEAP). As the name suggests, its brief is to report on the environmental impacts of ozone depletion. It operates as part of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). At the time it was chaired by Prof. Jan van der Leun, from Utrecht, Holland.

I became a member of the Panel, which now meets once per year to write interim assessments, and twice every 4th year when full Quadrennial Assessments are required. Starting with that meeting in Buenos Aires, there have been 30 Panel meetings to date. I’ve missed just two of them, one in South Africa and another in Spain, when the dates clashed with NIWA UV Workshops I was organizing in New Zealand.

Panel numbers vary from year to year, but there are usually about 30 to 40 members, who are asked to host the meetings in their home countries. For my first decade on the Panel, I was the only member from the Southern Hemisphere (though the geographic balance has been much better in recent years), so my travels have been further than most. I’ve attended meetings in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China (3 times), Germany, Greece (3 times), the Netherlands, India, Japan (3 times), Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand (4 times), Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, UK (3 times) and USA (2 times). A dozen of my trips with these Panels were essentially around-the-world trips.

New Zealand holds the record, with 4 meetings: one in Queenstown in 1996, one in Wellington in 2002, and two in my home town Alexandra. The first meeting in Alexandra was in 2006 and the second was the meeting just completed. Only two other countries in the world have hosted more Panel meetings than my small home town, with a population 5,000. I was always happier to host than to travel. And now I can claim some brownie points ….

I could pretend that I was always trying to minimize my carbon footprint, and that was indeed a factor in the later meetings. But my real motivation was that as time went on, I couldn’t be bothered with the strains and time-zone shifts of long distance travel.

It’s sobering and ironical to think of the environmental costs of that travel. Especially when we consider that the EEAP’s brief was extended in 2010 to include “and Interactions with Climate Change”. Through its control of CFCs, which are also potent greenhouse gases, the Montreal Protocol is credited with having the largest effect so far of any measure to minimize global warming. And its most recent Kigali Amendment in 2016 called for the complete phase-out of HFCs. These HFCs (i.e., hydrofluorocarbons) are replacements for the original CFCs and HCFCs that were used as refrigerants and foam blowing agents. Unlike the earlier chemicals, they contain no chlorine or bromine and have absolutely no effect on ozone - but they are strong greenhouse gases.

But at the same time as we take measures solve those problems, we fly dozens of scientists half way around the word each year to attend these meetings. How much does that contribute to global warming?

In 2017, the total global emissions of CO2 were 37,000 Mega tons. For a world population of 7.7 billion people, that’s about 5 tons per person. There’s a lot of variability between countries: for example, citizens from the USA are three times as bad as the global mean, while those from India are less than half as bad. But our carbon footprint is strongly dependent on standard of living, for which the range between panel members from different countries will be much smaller than the range between these countrywide means.

There’s a range of estimates for the carbon footprint from flying. One reputable web site estimates that for long-haul flights, the emission rate is about 0.1 kg of CO2 per km for economy-class passengers, or twice that if indirect effects are included. So, one around-the-world trip (40,000 km) for panel members like me travelling economy class amounts to between 4 and 8 tons of CO2 per year (and would be much higher for business-class of first-class passengers). While that’s small compared with the global emissions of CO2, we need to consider our contribution at an individual level. For me, my travel to UNEP meetings nearly doubles the carbon footprint I would have had without that travel.

And that’s not the only travel I should be counting. I’ve also attended dozens of symposia and workshops associated with ozone and UV in many other countries from the 1980s until my “retirement” in 2012. But even ignoring those, my personal carbon footprint from air travel associated with participation in these Panels alone over the last 4 decades is comparable with the lifetime footprint of the average global citizen. And it far exceeds that of citizens from the most at-risk countries like Bangladesh. While I may have contributed in a small way to solving the ozone problem, my activities in doing so have hindered solving the problem of global warming. From the Planet’s point of view, it would have been much better, once the technology became available, to carry out those duties through videoconferencing and emailing.

I’m happy to report that, as from last week, the UNEP travel contribution to my global warming footprint has now ceased. I officially handed in my notice at the meeting just finished.

I’d be even happier if my son and his family moved back from USA to New Zealand to obviate our desire to travel there (especially when that country is so recklessly presided-over by low-life brats).

Let tRump’s youngest nemesis, Greta Thunberg, be our example to follow.