The continuing story of “Saving our Skins”. Tragedy closer to home. Shorter, but not so sweet.

Updated September 5, 2021.

Memories of an inter-calibration campaign in the summer of 1993 are indelibly etched in my brain. Colleagues Colin Roy from Australia, and Gunther Seckmeyer from Germany had brought their UV spectrometers to Lauder, along with their own calibration lamps, so we could inter-compare our three measurement systems, including their calibration standards. To get enough output at UV wavelengths, powerful calibration lamps are needed. I clearly recall bemoaning the difficulties setting up the 1000 W lamp from Germany. It required a power supply manufactured in the USA that used 110 Volts, rather than the 230 Volts used in New Zealand. While the 110 Volt standard was safer, we knew what we were doing so that wasn’t a concern. But I was to change my mind on that very day: February 16, 1993.

By then we were living in Alexandra, having purchased our home at 14 Blackmore Crescent on our return from Oxford. As usual, I’d commuted to work that morning in the NIWA van. After work, I’d been dropped off around 5:30 pm on Centennial Avenue, at my usual drop-off point about halfway between our home and the local high school. It had been an unsettled summer, but this Tuesday was one of those stunningly sunny Central Otago days, with wall-to-wall blue skies. I immediately felt the heat of the sun beating down on me as I stepped out of the van. The day before, my son David had met me at that same spot on his way home from an after-school cricket practice. He was 14 and was the proud owner of a new 10-speed road bike that we’d bought him for Christmas. But he wasn’t there with it that day.

As I set off to walk the 500 metres to our home, I could see a car parked on the street outside the house. It was a grey 1984 commodore station wagon, and a rust patch on the bonnet told me that it belonged to our friend, Sue Macpherson. The same Sue Macpherson that we had first met in Oxford ten years earlier. Their family had moved back to New Zealand from Wales, and she was now a local GP. She often popped in to see us. As I neared our house, I passed our next-door neighbour, Wal Crawford, who was toting a couple of bottles of home brew across to another neighbour. He was strangely reticent, and hardly acknowledged my casual greeting and carefree banter about his questionable afternoon drinking habit.

I stepped inside our front door and saw Sue standing at the phone in the dining room. Her eyes were wide. Our precious son David was dead. I can’t remember her exact words, but her body language left no room for doubt.

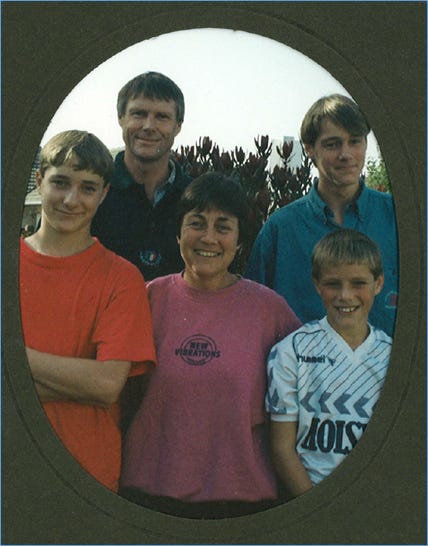

My world had changed for ever in a heartbeat. I was in complete shock and denial. And completely powerless. There was nothing I could do to fix this problem. No other family member was there. I felt empty and sick. I learned later that big brother Andrew had been sent to pick up Hamish who was playing softball at the time in the Molyneux Park sports fields right next to the High School ground. They had then gone to Macpherson’s place to keep them away from the tragedy that was unfolding, and Malcolm was still looking after them. Sue told me that Louise had gone to the hospital in nearby Clyde, trying to see if there was any hope. But Sue knew. She had been the emergency doctor, who had been called to the school to help the St Johns ambulance service.

He’d been pronounced dead at the scene, probably by our friend Sue, and the ambulance had taken him straight to the funeral parlour.

David had been at cricket practice, using the nets set up in the corner of the school sports grounds. A lusty hit from the batsman sent the ball sailing towards the centre of the ground. It was David’s job to run and retrieve it from its resting place alongside a cable tethered to a large travelling irrigator that was operating nearby. It was a sweltering day, and he probably welcomed the chance to cool off in the water that was lying all around. But, deliberate or not, we’ll never know because he never said another word. While retrieving the ball, he came into contact with the cable, which by a freak chain of events had become electrified with the mains supply voltage. The 230-volt power in New Zealand alternates at 50 cycles per second, a frequency that makes it hard to relax your muscles if you accidentally grip a live cable. He received a massive jolt that proved fatal.

It could have been even worse. It was sheer luck that others coming to his assistance didn’t suffer the same fate. One of his classmates, Shannon Morris, was also badly shocked, but he made a full recovery. Coincidentally, despite that close shave he went on to become an electrician himself, following his father’s career path.

The drama had unfolded shortly after I’d left Lauder on my way back to Alexandra. There were no cell phones then, and the way the local jungle telegraph worked I may have been one of the last in the town to hear about it. Later that evening the local police sergeant, Brian Seymour, knocked on our door. He’d come to officially notify us of David’s death. These tasks must be one of the most dreaded for police. In this case it must have been especially painful. It was personal. He was David’s long-time football coach and mentor. But by the time he arrived our house was already full, with friends and the whole Māori community that Louise embraced, offering support and condolences. At one point during the evening, the remaining four of us took time away to visit the morgue where David was lying on a slab. He was cold and looked to be asleep. There wasn’t a mark on his body.

How did it happen? With an annual rainfall of around 250 mm (10 inches) in the town, irrigation is needed to keep the grass growing in summer. The travelling irrigator in the school grounds was an ingenious self-propelled device. To set it up, a drum of steel cable is unwound from its spool on board the irrigator. One end of the cable remains connected to the spool, and the other end is connected to a steel stake that is driven into the ground. High pressure water flows to the irrigator in a hose alongside the cable and is directed by nozzles which cause the sprinkler to rotate. This rotation in turn drives the winch spool, which, over a period of hours, pulls the irrigator towards the stake.

But the stake had been driven through a buried electrical cable. Normally, this can’t happen because cables are buried at least 600 mm (2 feet) below the surface. And even if it could happen, it wouldn’t be a problem because the co-axial construction legally required for buried cables would make it unlikely that electrocution can occur. But this cable was not legal. It had been laid years before to provide power to a Public Address system that was used for the school’s annual athletics day. It was laid by volunteers, and to save time and costs, was buried just a few centimetres below the surface. And instead of using a co-axial cable, they had used what we call “true rip” cable, with side-by-side conductors.

I sometimes wonder if the accident was predestined by some greater force. It’s not that I really believe in that sort of thing, but the circumstances get even eerier. The circuit containing the forgotten cable was troublesome. During his regular checks, the school’s electrician, Phil Morris – father of the next boy on the scene who was lucky not to be electrocuted as well - often had to repair the fuse. He had repaired it just a few days before. What’s more, the cable would not usually have been live at that time of day. The switchboard containing the fuse to that circuit was in the woodwork classroom, and because the machines there are potentially hazardous the main switch normally was turned off after school each day. But on this day the regular teacher was away, and the relieving teacher was unaware of that duty of care. Normally, the cable would have been safely isolated, but not this day. The electricity and water were a recipe for disaster.

He died two months short of his 15th birthday. Everybody was in shock. We were devastated. Our family unit was destroyed. Among the many poignant messages that we received was an adaptation from Helen Steiner Rice penned by a classmate:

“Life is not measured by the years you lived

But by the friends you made and the things you did”

Those words can be read on a Memorial Stone in the grounds of Dunstan High School. We used David’s savings to set up a trust fund for an annual “Service to Others” prize in his memory at the school.

Our oldest son Andrew left home for Otago University the following year, leaving just three of the five at home.

We all struggled to cope. Louise devoted her time to family, friends and worthy causes. These include helping the disadvantaged, Māori students at Dunstan High School, and the wider Māori community. You find who your friends are at times like this. Two lovely ladies, Jan Pessione and Wilma Paulin, had travelled the same path years earlier and we helped them to set up a local group to provide support for bereaved parents. It’s called the “Central Otago Compassionate Friends”: the club that nobody wants to join. Sadly, it’s still needed now, 25 years later. Louise still helps with visits, while I am the long-suffering treasurer. Andrew is now the same age we were when his brother died.

I now understood exactly what Richard Dawkins was driving at in his works, starting with The Selfish Gene. I don’t remember much about the next few years, and I apologise for my neglect of others. I was in survival mode. My life is forever punctuated by David’s death: years before, and years after (we are now almost exactly halfway through this book too).

To this day I’m still tortured with unanswerable questions. Why him? How many small decisions could have averted his death? Why did he die when he still looked so perfect in death? Would he still be alive if our mains voltage had been 110 Volts instead of 230 Volts?

Did he even have to die that afternoon? There were no publicly available heart defibrillators in town then, but nowadays there are dozens, including one at the school only 100 metres from the accident site. Could he have survived if there’d been one close-by then?

As an escape, I buried myself in my work. It was time to “do some things”. For a time I thought I’d never laugh or smile again. But I was wrong. Though the grief will always be with me, I’ve learnt to put it aside at times. At work, when I return to my office after our morning or afternoon tea-break, I often announce loudly that I’m going to “push back the frontiers of science”. I’m really just trying my hardest to do some of those things. While the rewards may be modest, I’m comforted in the knowledge that the things I do are things worth doing.

Next week. Catharsis through the things we did …