Concluding “Saving our Skins”, my personal back story of life before Lauder.

Updated September 5, 2021.

I’m nearing the end of a career in atmospheric sciences that’s so far spanned more than 40 years. I’ve been part of a revolution in the way science is conducted. Hopefully the preceding chapters have adequately chronicled my main work at Lauder. Here I’ll fill in a few details outside that period.

After leading NIWA’s radiation programme from its inception, I accepted a redundancy offer in 2012 when funding was scarce and the future for atmospheric science looked grim. That was a truly liberating experience. Since then I’ve retained a NIWA computer, an office at Lauder and access to the NIWA library and IT resources. I’ve been able to concentrate on the science without having to deal with the mountain of administrative bullshit and the ongoing battles with seeking funding, then writing the accountability report for that funding that spoils science research, and so many other vocations nowadays. The freedom has allowed me to do some exciting consultancy work for L’Oréal and others. In 2018 I also convened the last (?) of several UV Workshops, continuing a quadrennial series that started in the early 1990s. The spare time since then has allowed me to put together the story of “Saving our Skins”.

My favourite claim to fame precedes my birth by nine months. I’m proud to say that I must have been one of the last to be (legitimately) conceived in the old coal mining town of Denniston, high on a desolate plateau near Westport. A town, if you can still call it that, made famous by Jenny Pattrick’s novel, The Denniston Rose. At the time of my conception close to Christmas Day in 1949, it was still a thriving coal mining town. There were two ways of getting there. One was by a winding gravel road, that was so steep in parts that cars had to use reverse gear to get up. The other was the famously steep and scary “Denniston incline”, which descended 518 metres in a track distance of 1670 metres. It had been constructed to transport coal wagons but was sometimes in those pre-OSH-days used by the hardy - or perhaps foolhardy - inhabitants to go up and down the hill.

My dad, Don McKenzie, was the sole-charge teacher there. They didn’t have a car, and my Mum, Joan McKenzie (née Gregory), was nervous about using the Denniston Incline, especially after the birth in Westport of my older brother, Greg.

So, I’m confident that Denniston is where the deed was done. My Mum, who died not so long ago at age 92, used to just smile indulgently whenever I asked for her confirmation. I may have been a Christmas present.

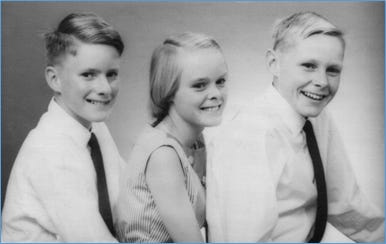

By the time I was born, on September 24, 1950, the family had already moved to Reefton, about 70 miles away, on the way to the Lewis Pass. Dad had taken a job at the District High School, which later became Inangahua College. Reefton was the first town in the southern hemisphere (no less) to have reticulated electricity. That was in 1888. That power station was decommissioned in 1949 when Reefton was connected to the national grid. So, we had electricity, but no refrigerator, and no TV of course. I was well into my teens by the time we got one of those. My sister Joanne was born there (no coincidence).

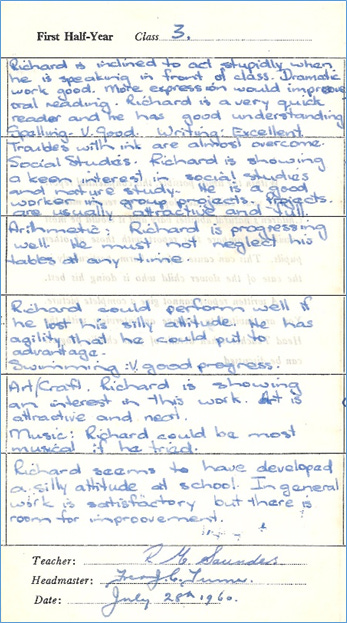

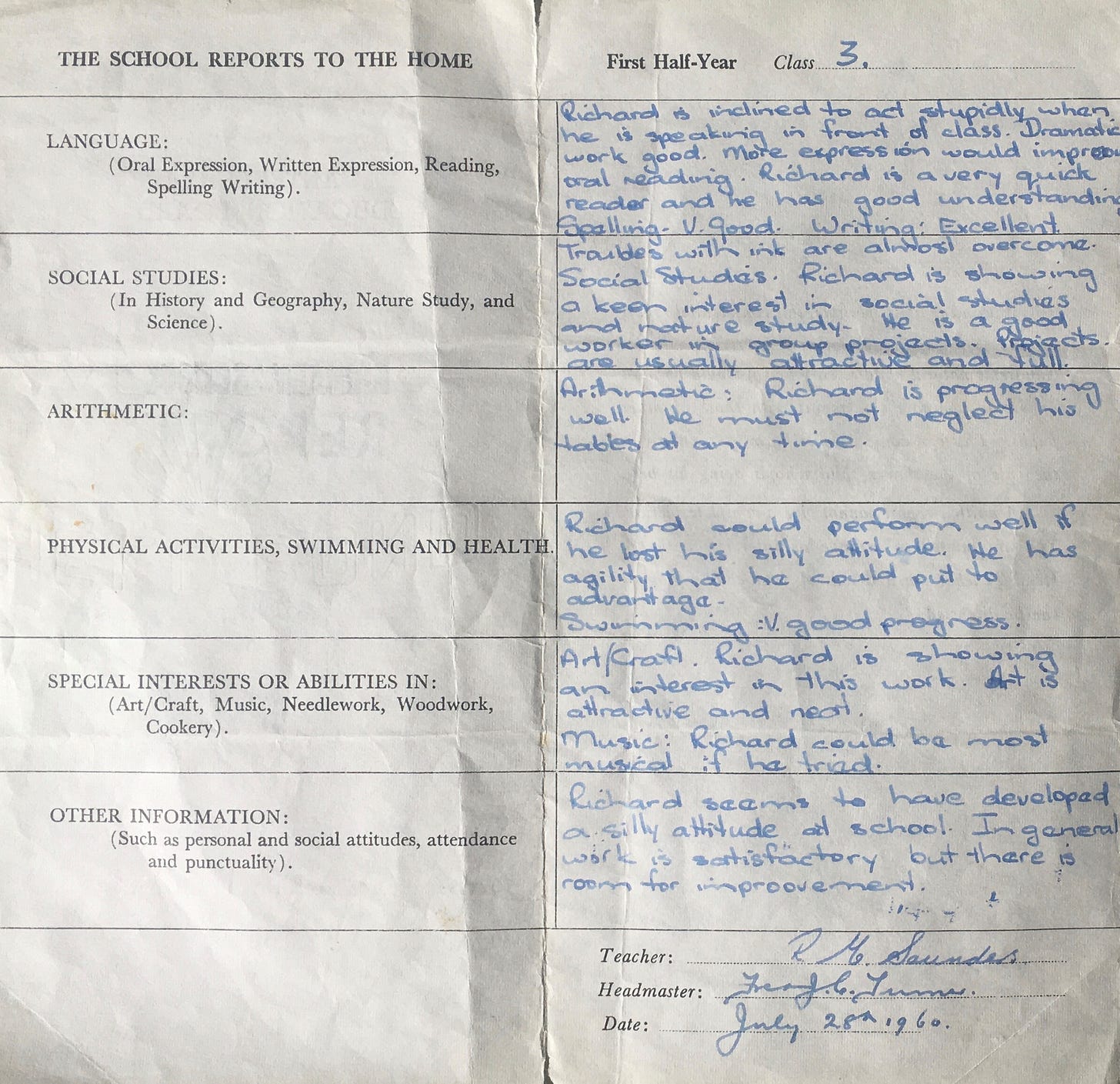

We moved “across the hill” to Darfield in 1959, when I was still at primary school. I definitely wasn’t a model student. Judging by my mid-year school report for 1960, it seems I had a few behavioural issues, with several refences to my ‘stupid’ attitude. Sadly, teachers nowadays would probably be sacked for being so blunt.

But I’m happy to say that my end-of-year report was more positive, showing the teacher’s comments must have had the desired salutary effect. Some may beg to differ, saying nothing much has changed even 60 years down the track. I was amused to read her caveat on my writing skill being OK “especially for a left hander” in that end-of-year report. Those were the days!

In 1965 we moved again, to the newly formed Ashburton College, which was an amalgamation of two warring schools in the area, making it one of the largest schools in the country at the time. I completed my senior high school years there. Mum and Dad were both quite high up the college feeding chain. They stayed on there for many years after we kids had all left home. Dad became interested in politics and must be one of very few people to have stood as a candidate in general elections for three different parties. He never made it to the House of Parliament in Wellington but played big roles in local politics. He also found an entrepreneurial streak, and he and a friend started a company called R-X Plastics. The company still thrives today, but unfortunately, our family no longer have any financial interest in it.

Then on to the University of Canterbury to do the engineering intermediate year. My grandfather, William Henry Gregory, was a successful electrical engineer with State Hydro Engineering. He was an interesting character. Pop to us, but also to many of his staff. He was quite a tyrant, I gather, and a strict teetotaller. He was an Australian by birth and had met my English grandmother while studying in Manchester. Her name was Florrie Wilkinson, from nearby Accrington – Coronation Street country.

The family plan was for me to follow my grandfather’s footsteps as an electrical engineer. He had worked on many of the hydro-electric schemes that had been built since the 1920s after they had arrived in New Zealand from Canada. My Mum had been born in Toronto, at the outset of their travel back from Canada to Australia. Pop couldn’t find a job in Australia, so they had moved to New Zealand to work on the Mangahao power station near Shannon, which was commissioned in 1924. Interestingly in the context of this story, by 1931 he was working on the Tuai hydro-electric dam at Lake Waikaremoana. The family were all shaken by the magnitude 7.8 earthquake at nearby Napier on February 3, 1931. The death toll from the quake was just one fewer than for the crash of flight NZ901 at Mount Erebus half a century later. My mum was seven years old at the time. Eighty years later she also experienced the 6.2 magnitude quake in Christchurch on February 22, 2011, which killed 185 people, making it New Zealand’s 5th deadliest disaster.

During a visit to Sri Lanka in 2012, I noticed a statue of a previous Governor of Ceylon – as it was then called - with the same name as my grandfather. I tried to find out if there was a link to Pop’s family but kept hitting dead ends. At the time he was born, records of births were not compulsory in Australia.

Much more was known about his famous namesake, who was born in 1816 and died in 1892. According to Wikipedia, he was “addicted to horse racing, which led to financial difficulties throughout his life”. He retired from the Ceylon office in 1877 and returned to England via Australia. He was eventually knighted for his services to the Empire.

According to our family records, my grandfather of the same name was born in Castlemaine, Victoria Australia in 1892. Could his mother, Mary-Jane Mudge have been the illegitimate daughter of the colourful Governor? His first wife had died in 1873 and he remained single until marrying his second wife in 1880. She later became famous in her own right as Augusta, Lady Gregory: an Irish dramatist and writer. It was she who compiled his biography that’s paraphrased on Wikipedia. It would not surprise me if he had forgotten to mention past liaisons of this kind to her. It’s just speculation, but if there really were a link, it would go some way towards explaining Pop’s puritanical views on drinking and gambling. And could I be the inheritor of a lost fortune?

Sadly, that’s probably not the case. Our family tree has Pop being fathered by one Edward Joseph Gregory, who was born in 1858. So perhaps his namesake was just visiting family on his way back home from Ceylon. But you never know. We have no record of Edward’s death. Anyway, my mum always admonished me not to dig too deeply into our family history because I may not like what I find. Maybe old William was the undeclared father, or maybe just his name was recycled in the family. Or maybe neither.

Talking about Australian connections, I should perhaps mention that dad’s mother Mary - or Molly – née Lowe was also from Australia. She hailed from Launceston, Tasmania. Real convict country. She and her sister Nellie emigrated to New Zealand while still in her teens. I imagine there must have been some excitement on the wharf at Riverton when these two attractive young adventurers stepped ashore. There she met my grandfather, Arthur Armstrong McKenzie, the only true kiwi in my family of that generation. He was a humble drover. I haven’t mentioned the Australian connection to many people, but with two grandparents being born in Australia, that makes me half Australian. I’m bound to have some convict blood! But admitting my Australian heritage (if you can call it that) would spoil a lot of my banter. All Kiwis love taking the piss out of Australians. It’s all just part of our social cringe.

Q. What’s the definition of an Australian aristocrat?

A. An Aussie who can trace his ancestry right back to his father.

But I rebelled after my first year at the University and failed to follow Pop’s career path. My grades were good enough, but instead of carrying on in engineering, I accepted an invitation by the physics department to join their honours class. Flattery will get you everywhere with me. I don’t know how it happened, but three years after I managed to emerge with first class honours, and no further plans. I knew I didn’t want to carry on in academia. Oddly, I much later discovered that the physics department at Canterbury was quite active in atmospheric research, and had even become interested in ozone chemistry, way ahead of the time it became fashionable. It was only in my late career that I became aware that several of my more senior colleagues and managers had at that time been doing their PhD studies in such relevant areas then. Andrew Matthews, my later manager at Lauder, and Reid Basher, who went on to work for the New Zealand Met Service measuring ozone and UV radiation, had both worked on an instrument to measure atmospheric ozone. David Wratt and Murray Poulter, who both became senior managers at NIWA, were there too.

But I wanted out. A couple of years earlier, I had taken up a teaching scholarship, mainly because it gave enough money to keep me in comfort, with the knowledge that if I reneged on following up with teaching, I would only have to pay a small fraction of the money back. Life was different in those days. As it happened, I had nothing better to do on completing my degree, so I enrolled at Christchurch Teachers College, and majored in maths and physics, with minors in pool and golf. Such a hard life.

That was the same year, 1973, that Louise and I were married. She was a teacher too, as were her parents, her grandmother, and two of her brothers. We had met a couple of years earlier while she was holidaying in the South Island, with her long-time friend Helen Clarke (who went on to become New Zealand’s first elected female prime minister), during the August holiday break from teachers training college in Auckland. That meeting was in Ashburton, where her brother Ken worked with my dad. Dad was a keen amateur pilot, and later glider pilot, and Ken had arranged for him to take her flying over the alps. I happened to be visiting when he brought her back home. And the rest is history.

We’d continued our long-distance romance the following year when she was posted to the Bombay Hills in South Auckland. The next year she was to have been posted to Minginui Forest, in the back-blocks of the North Island - until we decided that we should continue our life together. She got a job teaching at Isleworth School in Christchurch.

After my year at Teachers College, I took a job teaching maths and physics at a brand-new high school in Kaiapoi, just north of Christchurch. My interview for the job was with the head of the maths department, Jim Adams, on the golf course. I wisely lost to him and got the job. We remain friends to this day, and I never managed to beat him at golf until very recently. He is now in his late 70s; and has several times achieved the golfer’s milestone of playing a round in a score less than his age. He’s done it at several courses, including several par-72 courses, but I’m sure his purchase of a holiday home at Hanmer Springs was influenced by the town having a lovely golf course, with a par rating of only 68.

We moved from our flat on Bealey Ave to a cottage at Stewarts Gully, an off-beat settlement half-way between Christchurch and Kaiapoi. The cottage was very cute, but the toilet facilities were primitive. Louise was interrupted one night when the night cart man came by on his weekly round to collect our offerings.

The following year we bought our first house: a brand new 3-bedroomed ownership flat in Kaiapoi for $20,000. (We sold it in 1986 for $53,000, with the help of my dad, who was by then retired from teaching, and working in real estate). It’s not there now. Its address was 16 Gray Crescent, Kaiapoi, but the street numbering now starts at 32. About 40 houses including ours, were demolished after being irreparably damaged by the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010 and 2011.

Our first son Andrew arrived soon after we moved to Kaiapoi. He was born in nearby Rangiora, the “best doing baby in the hospital” according to the ward nurse of German descent. I was lucky to escape from Kaiapoi High when Jim Adams and his wife Kath, rushed around to our place one Saturday morning to say they’d found the perfect job for me advertised in The Christchurch Press newspaper.

In their eagerness to set me on a different path, they must have provided a good reference. So, it was out of teaching and into a lecturing job at the University of the South Pacific in Suva. Not a particularly good advertisement for my teaching abilities. They say that “if you can’t do, you should teach, and if you can’t teach you should lecture”. Maybe it’s true I can’t “do” much. But I’m sure my teaching would have improved with time, as teaching runs in the family blood.

.

Concluding Remarks for Family

That’s the back story of how we ended up in Fiji before the start of our association with Lauder. I was fortunate to be there over those years and able to play a small part in such a worthwhile endeavour. I consider this book as the next episode in a family history that was begun by my mum with her “Joan’s Story”. She finished it in her late eighties, with a lot of help from my sister Joanne. I’m glad I could put this part of our family story together before it was too late. Another family record that might be of interest is one my dad wrote when David died. He called it “The Farewell”. I’ve made soft copies of it for safe keeping, and recently posted it at https://uv.substack.com). My uncle, Morris Johnstone, who died just before his 98th birthday in 2019, has also written up a history for his side of the family. On his return to New Zealand after serving in WW2, he worked as an electrical engineer in a coal mine at Denniston where my parents introduced him to my mum’s sister Shirley. He’s been part of our family ever since. He later became a teacher, and their first child, Annette, was born just down the road from us at Clyde Hospital, when he was teaching in Alexandra in 1952.

Finally, the “”Christmas” letters that I touched on in Chapter 7. Every year since our days in Oxford in the mid-1980s, we’ve produced an update of our activities to distribute to friends and family. We write them in lieu of the usual banal Christmas cards, and normally send them out some time between Christmas and New Year. The activity became much easier (and popular among others) after the advent of e-mail. All those files should be findable. They are named Xmasyy.*, where yy is a 2-digit representation of the year (since they predate the realisation of the famous Y2K problem which emerged near the end of the 20th century).

*****

I’m nearing the end of a career in atmospheric sciences that’s has so far spanned more than 40 years. I’ve been part of a revolution in the way science is conducted. Hopefully the preceding chapters have adequately chronicled my main work career at Lauder. Here I’ll fill in a few details outside that period.

After leading NIWA’s radiation programme from its inception, I accepted a redundancy offer in 2012 when funding was scarce and the future for atmospheric science looked grim. That was a truly liberating experience. Since then I’ve retained a NIWA computer, an office at Lauder and access to the NIWA library and IT resources. I’ve been able to concentrate on the science without having to deal with the mountain of administrative bullsh** and the ongoing battles with seeking funding, then writing accountability reporting for that funding that spoils science research, and so many other vocations nowadays. The freedom has allowed me to do some exciting consultancy work for L’Oréal and others. In 2018 I also convened the last (?) of several UV Workshops, continuing a quadrennial series that started in the early 1990s. https://www.niwa.co.nz/our-services/online-services/uv-and-ozone/workshops. The spare time since then has allowed me to put together the story of “Saving our Skins”.

My favourite claim to fame precedes my birth by nine months. I’m proud to say that I must have been one of the last to be be (legitimately) conceived in the old coal mining town of Denniston, high on a desolate plateau near Westport. A town, if you can still call it that, made famous by Jenny Pattrick’s novel, “The Denniston Rose”. At the time of my conception close to Christmas Day in 1949, it was still a thriving coal mining town. There were two ways of getting there. One was by a winding gravel road, that was so steep in parts that cars had to use reverse gear to get up. The other was the famously steep and scary “Denniston incline”, which had been constructed to transport coal wagons, but was sometimes in those pre-OSH-days used by the hardy - or perhaps foolhardy - inhabitants to go up and down the hill.

My dad, Don McKenzie, was the sole-charge teacher there. They didn’t have a car, and my Mum, Joan McKenzie (nee Gregory) was nervous about using the Denniston Incline, especially after the birth in Westport of my older brother, Greg.

A group of school children, some no-doubt taught by my father a few years later, posing by the Denniston incline in 1944, with an empty coal wagon being pulled back up.

A more recent picture of wagon at the top of the disused incline on a rare clear day, overlooking the Tasman Sea below.

So, I’m confident that Denniston is where the deed was done. My Mum, who died not so long ago at age 92, used to just smile indulgently whenever I asked for her confirmation. I may have been a Christmas present.

By the time I was born, on 24 September 1950 our family had already moved to Reefton, about 50 miles away, on the way to the Lewis Pass. Dad had taken a job at the District High School, which later became Inangahua College. Reefton was the first town in the southern hemisphere (no less) to have reticulated electricity. That was in 1888. That power station was decommissioned in 1949 when Reefton was connected to the national grid. So, we had electricity, but no refrigerator, and no TV of course. I was well into my teens by the time we got one of those. My sister Joanne was born there (no coincidence). My schooling started there too, but we moved “across the hill” to Darfield, Canterbury, in 1959, when I was still at primary school. Judging by my mid-year school report for 1960, it seems I had a few behavioural issues.

Sadly, teachers nowadays would probably be sacked for being so blunt. But I’m happy to say that the end-of-year report was more positive, showing the teacher’s comments may have had the desired salutary effect. Some may beg to differ, saying nothing much has changed even 60 years down the track.

In 1965 we moved again, to the newly-formed Ashburton College, which was an amalgamation of two warring schools in the area, making it one of the largest schools in the country at the time. I completed my senior high school years there. Mum and Dad were both quite high up the college feeding chain. They stayed on there for many years after we kids had all left home. Dad became interested in politics and must be one of very few people to have stood as a candidate in general elections for three different parties. He never made it to the House of Parliament in Wellington but played big roles in local politics. He also found an entrepreneurial streak, and he and a friend started a company called R-X Plastics. The company still thrives today, but unfortunately, our family no longer have any financial interest in it.

Then on to the University of Canterbury to do engineering intermediate year. My grandfather, William Henry Gregory, was a successful electrical engineer with State Hydro Engineering. He was an interesting character. Pop to us, but also to many of his staff. He was quite a tyrant, I gather, and a strict tee-totaller. He was an Australian by birth and had met my English grandmother while studying in Manchester. Her name was Florrie Wilkinson, from nearby Accrington – Coronation Street country. The family plan was for me to follow my grandfather’s footsteps as an electrical engineer. He had worked on many of the hydro-electric systems that had been built since the 1920s. They had arrived in New Zealand in the 1920s, having come from Canada, where my Mum was born in Toronto, during their travel back from Canada to Australia. Pop couldn’t find a job in Australia, so they had moved to New Zealand to work on the Mangahao power station near Shannon, which was commissioned in 1924. Interestingly in the context of this story, by 1931 he was working on the Tuai hydro-electric dam at Lake Waikaremoana. The family were all shaken by the magnitude 7.8 earthquake at nearby Napier on February 3, 1931. The death toll from the quake was just one fewer than for the crash of flight NZ901 at Mount Erebus. My mum was seven years old at the time. Eighty years later she also experienced the 6.2 magnitude quake in Christchurch on February 22, 2011, which killed 185 people, making it New Zealand’s 5th deadliest disaster.

During a visit to Sri Lanka in 2012, I noticed a statue of a previous Governor of Ceylon – as it was then called - with the same name as my grandfather. I tried to find out if there was a link to Pop’s family but kept hitting dead ends. At the time he was born, records of births were not compulsory in Australia.

Much more was known about his famous namesake, who was born in 1816 and died in 1892. According to Wikipedia, he was “addicted to horse racing, which led to financial difficulties throughout his life”. He retired from his Ceylon office in 1877 and returned to England via Australia. He was later knighted for his services.

According to our family records, my grandfather of the same name was born in Castlemaine, Victoria Australia in 1892. Could his mother, Mary-Jane Mudge have been the illegitimate daughter of the colourful Governor? His first wife had died in 1873 and he remained single until marrying his second wife in 1880. She later became famous in her own right as Augusta, Lady Gregory: an Irish dramatist and writer. It was she who compiled his biography that’s paraphrased on Wikipedia. It would not surprise me if he had forgotten to mention past liaisons of this kind to her. It’s just speculation, but if there really were a link, it would go some way towards explaining Pop’s puritanical views on drinking and gambling. And could I be the inheritor of a lost fortune?

Sadly, that’s probably not the case. Our family tree has Pop being fathered by one Edward Joseph Gregory, who was born in 1858. So perhaps his namesake was just visiting family on his way back home from Ceylon. But you never know. We have no record of Edward’s death. Anyway, my mum always admonished me not to dig too deeply into our family history because I may not like what I find. Maybe old William was the undeclared father, or maybe just his name was recycled in the family. Or maybe neither.

Talking about Australian connections, I should perhaps mention that dad’s mother Mary - or Molly – née Lowe was also from Australia. She hailed from Launceston, Tasmania. Real convict country. She and her sister Nellie emigrated to New Zealand while still in her teens. I imagine there must have been some excitement on the wharf at Riverton when these two attractive young adventurers stepped ashore. There she met my grandfather, Arthur Armstrong McKenzie the only true kiwi in my family of that generation. He was a humble drover. I haven’t mentioned the Australian connection to many people, but with two grandparents being born in Australia, that makes me half Australian. I’m bound to have some convict blood! But admitting my Australian heritage (if you can call it that) would spoil a lot of my banter. All Kiwis love taking the piss out of Australians. It’s all just part of our social cringe.

Q. What’s the definition of an Australian aristocrat?

A. An Aussie who can trace his ancestry right back to his father.

But I rebelled after my first year at the University and failed to follow Pop’s career path. My grades were good enough, but instead of carrying on in engineering, I accepted an invitation by the physics department to join their honours class. Flattery will get you everywhere with me. I don’t know how it happened, but three years later I managed to emerge with first class honours, and no further plans. I knew I didn’t want to carry on in academia. Oddly, I much later discovered that the physics department at Canterbury was quite active in atmospheric research, and had even become interested in ozone chemistry, way ahead of the time it became fashionable. It was only in my later career that I became aware that several of my more senior colleagues and later bosses had at that time been doing their PhD studies in such relevant areas then. Andrew Matthews, my later boss, and Reid Basher, who later worked for the NZ Met Service measuring ozone and UV radiation, had both worked on an instrument to measure atmospheric ozone. David Wratt and Murray Poulter, who both became senior managers at NIWA, were there too.

But I wanted out. A couple of years earlier, I had taken up a teaching scholarship, mainly because it gave enough money to keep me in comfort, with the knowledge that if I reneged on following up with teaching, I would only have to pay a small fraction of the money back. Life was different in those days. As it happened, I had nothing better to do on completing my degree, so I enrolled at Christchurch Teachers College, and majored in maths and physics, with minors in pool and golf. Such a hard life.

That was the same year, 1973, that Louise and I were married. She was a teacher too, as were her parents, her grandmother, and two of her brothers. We had met a couple of years earlier while she was holidaying in the South Island, with her long-time friend Helen Clark (later New Zealand’s first elected female prime minister), during the August holiday break from teachers training college in Auckland. That meeting was in Ashburton, where her brother Ken worked with my dad. Dad was a keen amateur pilot, and later glider pilot, and Ken had arranged for him to take her flying over the alps. I happened to be visiting when he brought her back home. And the rest is history.

We’d continued our long-distance romance the following year when she was posted to the Bombay Hills in South Auckland. The next year she was to have been posted to Minginui Forest, in the back-blocks of the north Island - until we decided that we should continue our life together. She got a job teaching at Isleworth School in Christchurch.

After my year at Teachers College, I took a job teaching maths and physics at a brand-new high school in Kaiapoi, just north of Christchurch. My interview for the job was with the head of the maths department, Jim Adams, on the golf course. I wisely lost to him and got the job. We remain friends to this day, and I never managed to beat him at golf until very recently. He is now in his late 70s; and has several times achieved the golfer’s milestone of playing a round in a score less than his age. He’s done it at several courses, including several par-72 courses, but I’m sure his purchase of a holiday home at Hanmer Springs was influenced by the town having a lovely golf course, with a par rating of only 68.

We moved from our flat on Bealey Ave to a cottage at Stewarts Gully, an off-beat settlement half-way between Christchurch and Kaiapoi. The cottage was very cute, but the toilet facilities were primitive. Louise was interrupted one night when the night cart man came by on his weekly round to collect our offerings.

The following year we bought our first house: a brand new 3-bedroomed ownership flat in Kaiapoi for $20,000. (We sold it in 1986 for $53,000, with the help of my dad, who was by then retired from teaching, and working in real estate). But it’s not there now. Its address was 16 Grey Crescent, Kaiapoi, but the street numbering now starts at 19. The first 18 houses, including ours, were demolished after being irreparably damaged by the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010 and 2011.

Our first son Andrew arrived soon after we moved to Kaiapoi. He’d been born in Rangiora, the “best doing baby in the hospital” according to the ward nurse of German descent. I was lucky to escape from Kaiapoi High when Jim Adams and his wife Kath, rushed around to our place one Saturday morning to say he’d found the perfect job for me advertised in The Christchurch Press newspaper. So, it was out of teaching and into a lecturing job at the University of the South Pacific in Suva. Not a particularly good advertisement for my teaching abilities. They say that “if you can’t do, you should teach, and if you can’t teach you should lecture”. Maybe it’s true I can’t “do” much. But I’m sure my teaching would have improved with time, as teaching runs in the family blood.

That’s the back story of how we ended up in Fiji before the start of our association with Lauder.

Consider this back story as the next episode in a family history “Joan’s Story” that was begun by my mum. She finished it in her late eighties, with a lot of help from my sister Joanne. I’m glad I could put this update together before it was too late. Another booklet that might be of interest is the one my dad wrote when David died. He called it “The Farewell”. I’ve made a soft copy of it for safe keeping. My old Uncle Morris (Johnstone), who died just before his 98th birthday in 2019, has also written up a family history. He fought in WWII, and on his return to New Zealand, he worked as an electrical engineer in a coal mine at Denniston. My parents introduced him to my mum’s sister Shirley, and he’s been part of our family ever since. He later became a teacher, and their first child, Annette, was born at Clyde Hospital, when he was teaching in Alexandra in 1952.

That’s it for the present (apart from a final acknowledgment section that will come out tomorrow). Thanks very much for sticking with me for the whole nine yards … If you want more details, please feel free to post comments at Substack, or send me an email. I’ll be continuing with occasional blogs, and you’re very welcome to subscribe. There’s no cost!