Skin cancers avoided (and not avoided) by ozone controls

More on the success story of the Montreal Protocol ...

I’ve just discovered - or perhaps re-discovered (oops) - that my colleague Sasha Madronich and others published a very interesting paper last year on behalf of the US Environmental Protection Agency. Its title is a mouthful: “Estimation of Skin and Ocular Damage Avoided in the United States through Implementation of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer”. The main focus is on how many extra cases of these ailments are expected as a result of the two or three decade delay between ozone depletion beginning in the 1970s and the current controls being implemented. But it also looks into how many extra cases there would have been with the original 1987 version of the Montreal Protocol, and in the ‘world avoided’ with no controls at all.

That was the part I was most interested in. I’ve been trying to persuade colleagues in The Netherlands to update their 1996 Nature paper on the subject, where they calculated the number of cases avoided world-wide for all types of skin cancer. Their original article is behind a paywall, but the results were reproduced here (in Figure 15-1 of that report).

I was surprised that last year’s paper on the same subject didn’t receive more attention. Perhaps that’s because it appeared in a specialist journal Earth Space Chemistry published by the American Chemical Society, rather than a high impact journal like Nature that’s targeted more towards the general public.

It’s an impressive piece of work. Although it has its limitations, the results are well worth a look.

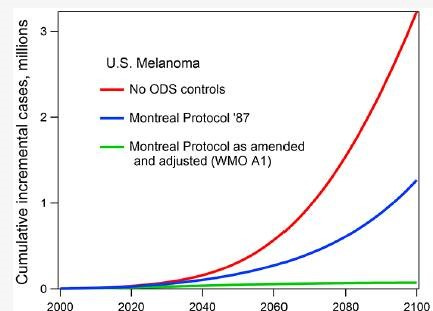

Living in the Melanoma Capital of the World (a title now held jointly with Australia), I’m most interested in the melanoma part of the story. From that perspective, the bottom line of the paper is summarised by the figure below, which appeared as part of the abstract, but puzzlingly was not discussed in detail in the main text (perhaps because the authors realised that most readers never get past the abstract 😊). But I think it’s important, so I’ll have a go at interpreting it here, especially in the New Zealand context. There was no caption with the plot, and I must admit that at first I misinterpreted it. I have to thank Sasha for his patience in an exchange of e-mails that eventually put me on the path to redemption.

The three curves show the cumulative increases above the 1980 baseline in melanoma cases over this century for the USA, calculated for three scenarios:

Without any controls on ozone depleting substances, i.e., if the Montreal Protocol had never come into force (red line at top)

With the original 1987 version of the Montreal Protocol (blue line at centre), and

With full implementation of the current version of the Montreal Protocol, including adjustments and amendments subsequent to the original 1987 agreement (green line at bottom).

The important message is that without any controls (red line), the cumulative number of melanoma cases in the USA would have increased rapidly above that 1980 baseline. Because of melanoma’s long gestation period, any differences between those three scenarios are still quite small at present, but by 2060 there would have been half a million more cases in the USA without any controls, and by the end of the century there would have been 3 million more cases.

If we’d stayed with the 1987 version of the Montreal Protocol (blue line), it would have been better, but there would still have been another million cases by century’s end. Those adjustments and amendments made to the Protocol since 1987 have been a vital part of its success. Without them, chlorine would have continued to increase, ozone would have continued to decline, and cancer rates would have continued their rise, albeit much more slowly than without any controls.

Successful though it is, there’s a human price to pay even with the current version of the Montreal Protocol (green line), because ozone is not expected to fully recover to 1980 levels until around the middle of the century. The extra cases from the increased UV exposure will reach their peak around the middle of the century. But the change is relatively small, amounting to about 100,000 extra cases.

How big are these changes compared with baseline levels? The paper tells us that there are about 70,000 cases per year in the USA. It doesn’t tell us how many extra cases per year, but for any year that’s just the local gradient of the curve. Using my trusty ruler as an aid, I estimate that by the end of the period shown, the USA would have been seeing an extra 100,000 melanoma cases per year. So, long before century’s end, the overall annual incidence would be more than double its current value every year. And it would continue to get worse. By contrast, with full compliance to the current regulations, the expected maximum rate of increase is much smaller: about 2,000 cases per year and only up to around mid-century.

How do New Zealand’s current rates compare? The numbers of cases are of course very different. In the USA, with a population of 330 million and 70,000 cases per year, the annual incidence rate is 200 cases per million per year. Our population is much smaller, but our rates are much higher. With a population of 5 million and 4,000 cases per year, our annual incidence rate here in the Melanoma Capital of the World is about four times as high as the USA’s at 800 cases per million per year. So we’re off to a bad start. Currently, about 350 of us die per year from melanoma, so our mortality rate is approaching 10 percent of the incidence rate (the same as in the USA).

How would New Zealand’s future rates have fared if there had been no Montreal Protocol? We can now estimate that because, as we’ve shown previously - increases in UV would have been at least as large in New Zealand as in the USA. New Zealand’s annual rate would therefore have more than doubled by around 2060. And the numbers would have continued to increase faster and faster had it not been for the Montreal Protocol (and its amendments and adjustments).

Those time horizons won’t affect me, but I’m very happy for the sake of my children and their descendants because there would have been twice as many melanoma deaths too, unless there were improvements in diagnosis and treatment. So, instead of the death rates being comparable with the current annual death toll from road accidents they would be twice as high (if cars still exist by then). By late in the century there would have been more than 500 extra deaths from melanoma every year in New Zealand.

And the problem would have continued to get worse ….

On a shorter time scale, between now and mid-century we should in New Zealand expect a total of ~6000 additional melanoma cases and about 500 extra deaths attributable to the delay in implementing the full Montreal Protocol (fewer than ten extra deaths from melanoma per year). For those and their loved ones, it will be cold comfort, but in the wider context that’s a small price to pay compared with the alternative. Well done Montreal Protocol, and well done Sasha and his colleagues for this useful work.

Finally, some comments on the limitations I mentioned earlier …

While the model Sasha uses is well suited to predicting the extra cases due to the delay in implementing the Montreal Protocol (the green curves), he would be the first to admit that it is not ideal for predicting cancer rates far into the world-avoided future when ozone amounts could have been less than one third of current levels. That’s because the model assumes that the relationship between ozone and the concentrations of ozone-depleting substances would have remained the same as over that entire period as for the period from 1979 to 1991. But the changes occurring in the second half of this century would have been in uncharted territory. As we showed in 2019, the relationship is far from constant. Without the Montreal Protocol, sunburning UV at mid latitudes would have increased by a ‘moderate’ 20 to 30 percent from 1980 to 2020, but by a factor of 2 or 3 in the next forty years, with a smaller increase in the last 40 years of the century.

The authors state that uncertainties in projected ozone changes alone are about fifty percent, and that the overall uncertainty in the excess numbers of cases is probably closer to a factor of two. It looks to me as if more work is needed on the subject, preferably using a more sophisticated model to predict the future ozone levels. Let’s hope that happens.

Of course the future number of deaths (or cases) predicted for New Zealand assumes a similar population growth rate as the USA’s, with no changes in ethnic diversity in the decades ahead. It also assumes no changes in diagnosis or treatment skills. All of these assumptions are doubtful. As has been said before, “It’s difficult to make predictions, especially about the future”.

I think all this is important, so I invite you to leave your comments below.

Hopefully it will become a discussion thread, so sign up below to stay tuned (there’s no cost).

Thanks for reading this. Previous posts on the intersection between Ozone, UV, Climate, and Health can be found at my UV & You area at Substack.