Events surrounding my introduction to Lauder about 40 years ago. I was 29 years old. Updated September 4, 2021.

Every Kiwi of my generation will remember November 28, 1979. For us, it’s one of those indelible dates; like November 22, 1963 when JFK was shot in Dallas, or September 11, 2001, when the Twin Towers fell in New York city in the “9/11” attacks. I know exactly where I was when I first heard the radio news those days. I also remember where I was on November 28, 1979, the day Air New Zealand flight NZ901 crashed into Mount Erebus in Antarctica, with the loss of 257 lives. It was, and still is, New Zealand’s most deadly peacetime disaster. Interestingly, New Zealand’s second worst peacetime disaster had just one fatality fewer. That was the magnitude 7.8 earthquake in Napier on February 3, 1931, where thousands more were injured.

Air New Zealand put the crash of the DC10 down to ‘pilot error’, but heads rolled within the company, after Justice Peter Mahon QC’s Commission of Enquiry famously described their version of the events as ‘an orchestrated litany of lies’. Strong words in the laid-back New Zealand of those times.

Before the “Erebus disaster”, as it became known in New Zealand, Antarctica had been off the radar for most, but not for me. My interest had just recently been piqued. Two weeks before, our family had moved back to New Zealand from Suva, Fiji, where I had been teaching at the University of the South Pacific. I recall in one of my lectures there, discussing the spectre of the “inevitable” future ice ages with my students. The time scales were over tens of thousands of years, and the projected cooling was due to well-documented changes in the orbital motion of Earth about the Sun - the so-called “Milankovitch” theory, named after the Serbian scientist who dreamt up the idea. The emphasis has changed a bit since those days. We now think that because of temperature rises expected due to increasing greenhouse gases the next ice-age may already have been averted.

Our new home back in New Zealand was to be in Central Otago near the tiny settlement of Lauder at a small outpost of DSIR, New Zealand’s Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.

Its existence was marked only by a small yellow finger-sign on a blind corner a couple of kilometres up the valley from the settlement. There, a narrow strip of sealed road wound off to the west. After crossing a noisy cattle-stop, the drive passed some stock yards on the right and a derelict wagon on the left, then continued for about half a kilometre before crossing another cattle-stop to the fenced-off area of the research post. The laboratory consisted of an eclectic collection of buildings, mostly old government Ministry-of-Works huts, but one substantial new office block that was in the process of being expanded. The road continued past them, veering left and passing a huge steerable antenna, before disappearing across a hill. Out of sight on top of the hill, away from any stray light from cars or buildings, was another smaller building, the optical laboratory which was used to observe the night sky. A branch-track off to the right carried on from the office past the staff housing area, consisting of a motley collection of five houses spread along a couple of hundred metres of road. Two were old wooden places with corrugated iron roofs. The other three were more modern houses with block walls and tiled roofs.

There were about 8 on the staff and 4 of them lived on-site. Our house was the closest to work, less than 50 metres from its main door. It was a modest, 3-bedroom place, but comfortable and cosy. It was only a year old and was sitting on bare land without fences.

My wife Louise was not particularly happy with the close confinement of such a small group. She got me to mark off an area of about 50 m by 50 m to be fenced off around the house for shelter and privacy. Plenty of room for the kids to play as well. As chief lawn mower, I had suggested a smaller area, but Louise won that battle.

The surrounding bleak treeless landscape made a sharp contrast with the lush vegetation in our previous life in tropical Suva. You get the idea from the photograph. We both wondered what we’d let ourselves in for with the move from our tropical paradise to this desolate spot. But we knew we had to get out of Suva. It’s easy enough to get one 3-year extension to USP contracts, but further extensions are more difficult because if you’re there for more than 7 years you can apply for Fiji citizenship. And the “powers that be” in the immigration department preferred that expats such as us didn’t have that option. In any case, they say you “go tropo” if you stay too long in the tropics.

It was my Mum who had spotted the job opportunity when we were nearing the end of my 3-year contract at the University. She lived about an hour’s drive south of Christchurch in Ashburton, which she had also suggested as a possible new destination for us after Fiji.

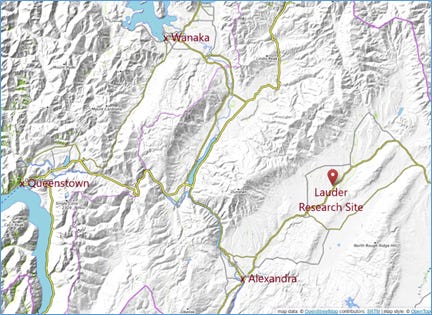

Her letter telling me of it accompanied a (since lost) clipping from the Situations Vacant section of the Christchurch Press newspaper advertising the scientist position at Lauder. She also attached a photocopied map of the Central Otago region with Lauder circled to show its relationship to Alexandra, Queenstown and Wanaka.

She was clearly keen to see more of her grandchildren. She and my Dad were still working at Ashburton College, where I had completed my own secondary school education in 1968. That included an introduction to a new style of teaching of physics, which had recently been introduced by the Physical Science Study Commission (PSSC) in the USA. My teacher in that formative class, Laurie Davies, was also my cricket coach. There’s no way I would have ended up being a physicist without the start that course gave me. The older “Halliday and Resnick”, or “Sears and Zemansky” style of textbooks, with their old non-SI units were not for me.

I applied for the post, and was asked to report for a job interview – but there in Suva, not Lauder. The interviewer was John Gabites. He was a colleague of the Lauder boss, Gordon Keys, and had previously been director of the New Zealand Meteorological Service. That was quite a coincidence because during a visit to Wellington the previous year, I’d asked his successor if they had any job openings there for me (they didn’t). Since his retirement a couple of years earlier Gabites had taken up the role as director of the newly independent Fiji Meteorological Service. During the interview he suddenly insisted that I leave at once and come back immediately with Louise. He was well aware of the isolation factor at Lauder and wanted to make sure we could both cope with that. On our return a few minutes later we had to laugh at the informality of it all because she didn’t have time to scrub up. She was still wearing jandals (flip-flops), and was carrying our baby (David) in her arms. The interview must have gone OK despite that because a couple of weeks later I received the job offer, which I (we?) gladly accepted. Soon after, we received another letter from Paul Johnston and his wife Carol. Paul was the acting officer-in-charge while Gordon Keys was away in Germany on sabbatical leave with his wife Rima (shortly after the death of their son, John). Included with their letter was the photograph below. I’m not sure if it was intended to warn us off, or just to make sure we were emotionally prepared for the change. The desolation of the bleak treeless landscape was palpable.

But we were undaunted. My first day of work at Lauder was November 11, 1979. I remember telling Paul that we’d probably be there for just a couple of years until our son, Andrew, started school. That was a serious error in judgement. He is now well into his 40’s, and I still go to my office at Lauder once or twice a week, even though I accepted a redundancy offer – including a (small) wheel-barrow-full of money - from my job there in 2012. Money for environmental research was in short supply then under a right-wing government.

It was grim for Louise but took less than a minute for me to walk to work, so it was no problem to come home for lunch and share time with her and our two sons. At that time our oldest son Andrew was nearly 3½ years old. Our second son, David - who was born in Fiji - was 19 months old.

Lauder Research Station (45S, 175E, altitude 370 m) and the Central Otago region Map credit: OpenTopoMap.

Louise quickly found teacher-relief work in several of the local schools. She was shoehorned on to the committee of the local pre-school kids play centre and was quickly voted in as the first - and only ever - female member of the Lauder Railway School Committee in its 80 years of existence. The sole-charge school was in decline. There were only 12 pupils and it would close about 7 years later when the roll fell to 4. We would be away in the UK with our kids at the time of the closure but had already announced we’d be moving to Alexandra on our return.

The laboratory was called the Lauder DSIR Auroral Station. The patrons of the local pub didn’t have a clue about what we did and referred to us as the “The Stargazers” (with heavy emphasis on the first syllable). In reality, that label wasn’t so far from the mark. Although we weren’t really concerned with the stars in the night sky, just about all our research at Lauder has been about the effects of the closest and brightest of them, the Sun.

Our real purpose was to take advantage of the southern location, clean air, clear skies, good horizon views, and lack of city lights, to study the “Aurora Australis”, or the “Southern Lights” as they are more commonly known.

While I learnt about the intricacies of upper atmospheric research involved in the aurora, my new managers generously allowed me time to complete a write-up of my master’s thesis from the University of the South Pacific. It was about tropical cyclones, which are a big deal for Fiji and forecasting their paths correctly can be a matter of life and death. My study investigated whether their paths were influenced by the temperature of the ocean surface beneath. We knew that sea surface temperatures greater than about 26°C were needed to sustain their intensity, but could small temperature gradients also induce shifts in their paths?

In the study, I used satellite-derived sea surface temperatures that had just recently become available. These temperatures were deduced from sensors on board a satellite that measured infrared emissions from the ocean surface hundreds of kilometres below. But we had also arranged to get sea surface temperature measurements more directly from merchant ships. For those, the temperature readings were from sampling buckets thrown overboard and hauled back, or from sensors for measuring the temperature for water cooling at the engine intakes. Like others, we noted differences between both ship-measured temperatures and satellite-derived values. The differences are usually attributed to the thin uppermost skin of the water having a lower temperature than the bulk water beneath. Of course, there was also the possibility that atmospheric effects had not been fully corrected. The people who wrote the algorithm to retrieve sea surface temperature from space would have had to deal with that, as it affects all satellite retrievals. Although I was less concerned about these atmospheric effects at the time, they would come to dominate my thinking in the years ahead.

It turned out that the paths of cyclones weren’t strongly affected by the ocean temperature. Other factors were more important. Neither was it relevant for New Zealand, so I was happy to move on.

My proposed research at Lauder was almost diametrically opposite to this earlier work in Fiji. Previously it was about sea surface temperatures influencing the paths of tropical cyclones in the atmosphere over the tropical Pacific Ocean. Now it was to be about solar activity influencing aurora hundreds of kilometres above the Earth’s surface in Antarctica.

With Lauder’s narrow focus on upper atmosphere research, and my own complete naivety, we had no inkling of the changes in store lower down in the atmosphere. Tragic though it was, the Air New Zealand plane crash in Antarctica that greeted my arrival at Lauder would pale into insignificance compared with the problems that were already starting to brew in the atmosphere about 20 km above. If that had played out fully, the annual death toll for skin cancer in New Zealand alone – let alone the rest of the world - would have exceeded that from the one-off air accident. Other environmental consequences would also have been far-reaching and disastrous. For example, the world’s fish supplies would have been disrupted by UV damage to oceanic phytoplankton, which is at the base of the aquatic food chain.

But like the rest of the world, we were blissfully unaware of these things. It’s true that the spectre of ozone depletion due to the break-down of CFCs had been raised by others, but on nothing like the scale that was to be seen soon in Antarctica. It was only a theory then; a theory being vigorously opposed by the manufacturers of the CFCs. There wasn’t widespread concern yet, and the knowledge was still largely confined to specialised areas of research.

Atmospheric scientists had recently become aware of another threat to the ozone layer - from the exhaust pipes of jet aircraft. But that wasn’t on our radar yet. We were still fixated on what was happening much higher up.

In next week’s instalment, “Sun, Earth and Radio” I’ll tell you a bit about the sort of work that was being done by the Star-gazers at DSIR Lauder in the early 1980s.