Welcome aboard all you captive-audience newcomers who subscribed after my talk in at the excellent UV & Skin Cancer Conference in Brisbane earlier this month. Sorry about the double posting that week, which was due to a scheduling error. I don’t normally inundate readers that way. Three or four times a month is plenty. I promised I’d substack (or should that be just ‘stack’?) all the stuff I presented in case anybody wanted a closer look. This one is about a related slide that I didn’t have time to discuss at all.

I was trying to explain why the UV dose is so much higher down under than in the UK. That plot from last time suggested that it’s about three times higher in Australia and New Zealand. One reason is the latitude difference. Our closer proximity to the equator means the sun rises higher in the sky making the absorbing atmospheric pathlength shorter. But that accounts for less than half the discrepancy.

Differences in ozone and seasonal changes in Earth-Sun separation are also important. These lead to calculated summer UV doses being another 15 percent more in the southern hemisphere compared with similar latitudes in the north.

But we’re still a long way short of that factor of three difference. Actual differences are much larger because of the effects of clouds and aerosols, both of which favour higher UV in Australia (and NZ to a lesser extent) compared with the UK. I’ll talk here about clouds.

Contrary to health promotion messages on UV safety, clouds do reduce the amount of UV we experience. But only if the clouds obscure direct sunlight. So, only if you can’t see your shadow. That’s a good rule of thumb to keep in mind.

Under partly cloudy conditions with the sun unobscured (so you can see your shadow), the UVI can be 20 percent more than for clear skies. But those enhancements are usually brief, and over longer periods they tend to be balanced by lower values when clouds obscure direct sunlight. So, averaged over a day, cloud-induced reductions in UV are likely only when there’s more than 50 percent cloud cover (so the sun is obscured by them more than half the time). So, that 50 percent cloud cover is an important threshold (which I really should test further with real data).

On the other hand, under overcast conditions, the amount of UV transmitted is typically only half of that for clear skies, or less. So, the duration of cloud cover really does matter. The point the health messaging is trying to make is that protection is still needed under cloudy skies, which is usually correct. If the amount of UV is halved under overcast skies, there can still enough in a day to cause 15 doses of skin-reddening UV for fair-skinned people. That’s enough to damage even the darkest skin types.

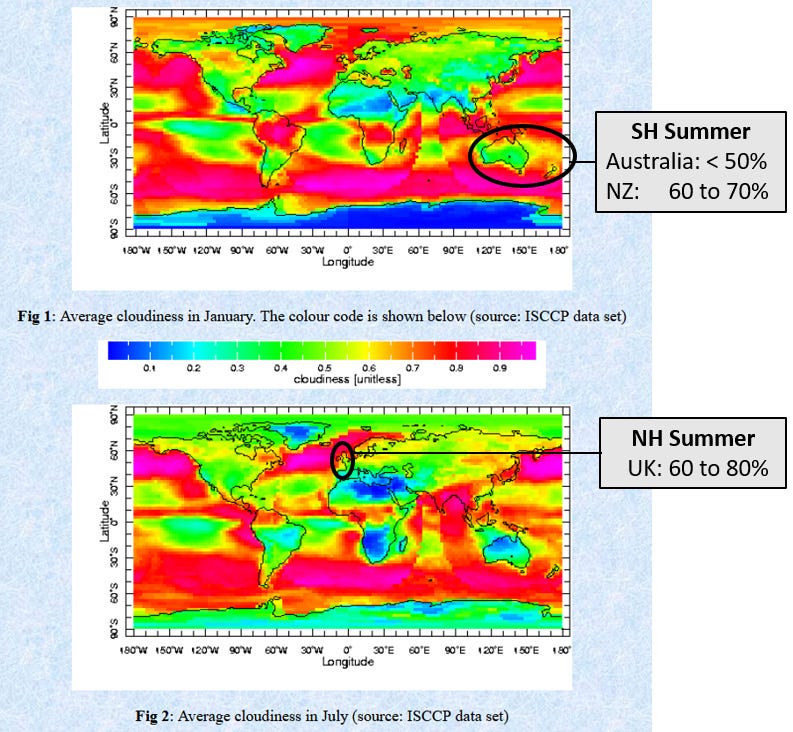

So, how do global patterns in cloudiness affect things? The maps below show average cloud amounts over the globe amounts for the months of January (at top) and July (at bottom), as put together by the International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project (ISCCP). The contours range from blue, corresponding to regions that are largely cloud-free, through to purple, corresponding to regions where there is more than 90 percent cloud cover.

For UV damage, it’s the summer that matters, as highlighted in the plots. The upper plot is for the southern summer (January), and the lower one is the northern summer (July). As you can see (and might have guessed 😊), it’s much less cloudy in Australia. The green shading in summer shows that over most of Australia, there’s less than that critical 50 percent cloud cover threshold that I mentioned above. In contrast, the red and yellow shading over the British Isles shows that cloud cover is typically greater than 60 percent in summer.

It’s much less cloudy in continental areas. The maritime climate of the UK (and New Zealand to some extent) is a big factor because there’s typically more cloud over oceans than land. The caveat for New Zealand is because of its topography. Some areas, particularly the Central Otago region where I live, are surrounded by mountains and have a more ‘continental’ climate. These small regional differences aren’t fully resolved in the global map.

Australia’s sunnier skies are clearly an important factor, but differences in cloud cover between the British Isles and New Zealand seem surprisingly small (especially after having experienced life in both places 😊). Perhaps the higher-than-expected UV differences there are more down to the aerosols? More on that next time.

Thanks Richard, very interesting as usual!

When you say:

"Contrary to health promotion messages on UV safety, clouds do reduce the amount of UV we experience."

Do you take into account UVAs as well? As far as I know they are not as affected as UVBs in this scenario or are they?

I've read in another post of yours that the UVI could even decrease by more than 50% if the sun is completely obstructed by clouds, but how much is the minimum decrease? Meaning, if the clouds are just enough to keep my shadow from appearing, is it a 50% decrease in that case or what?

I'm just trying to figure out a minimum percentage to use, so for example if the UVI is 4, I know that with clouds I always get 2 or less, and I plan my sun protection accordingly, so maybe, in that case, if I stay out for 1 hour, I know I won't get 1MED even without sunscreen.